Introduction to Ideal: The Play

by Leonard Peikoff

Ideal was written in 1934, at a time when Ayn Rand had cause to be unhappy with the world. We the Living was being rejected by a succession of publishers for being “too intellectual” and too opposed to Soviet Russia (this was the time of America's Red Decade); Night of January 16th had not yet found a producer; and Miss Rand's meager savings were running out. The story was written originally as a novelette and then, probably within a year or two, was extensively revised and turned into a stage play. It has never been produced.

After the political themes of her first professional work, Ayn Rand now returns to the subject matter of her early stories: the role of values in men's lives. The focus in this case, as in “Her Second Career,” is negative, but this time the treatment is not jovial; dominantly, it is sober and heartfelt. The issue now is men's lack of integrity, their failure to act according to the ideals they espouse. The theme is the evil of divorcing ideals from life...

Prologue

Office of Anthony Farrow in the Farrow Film Studios

Late afternoon. Office of ANTHONY FARROW in the Farrow Film Studios. A spacious, luxurious room in an overdone modernistic style, which looks like the dream of a second-rate interior decorator with no limit set to the bill.

Entrance door is set diagonally in the upstage Right corner. Small private door downstage in wall Right. Window in wall Left. A poster of KAY GONDA, on wall Center; she stands erect, full figure, her arms at her sides, palms up, a strange woman, tall, very slender, very pale; her whole body is stretched up in such a line of reverent, desperate aspiration that the poster gives a strange air to the room, an air that does not belong in it. The words “KAY GONDA IN FORBIDDEN ECSTASY” stand out on the poster.

The curtain rises to disclose CLAIRE PEEMOLLER, SOL SALZER, and BILL McNITT. SALZER, forty, short, stocky, stands with his back to the room, looking hopelessly out of the window, his fingers beating nervously, monotonously, against the glass pane...

Act 1 - Scene 1

Living room of George S. Perkins

When the curtain rises, a motion-picture screen is disclosed and a letter is flashed on the screen, unrolling slowly. It is written in a neat, precise, respectable handwriting:

Dear Miss Gonda,

I am not a regular movie fan, but I have never missed a picture of yours. There is something about you which I can't give a name to, something I had and lost, but I feel as if you're keeping it for me, for all of us. I had it long ago, when I was very young. You know how it is: when you're very young. You know how it is: when you're very young, there's something ahead of you, so big that you're afraid of it, but you wait for it and you're so happy waiting. Then the years pass and it never comes. And then you find, one day, that you're not waiting any longer. It seems foolish, because you didn't even know what it was you were waiting for. I look at myself and I don't know. But when I look at you—I do.

And if ever, by some miracle, you were to enter my life, I'd drop everything, and follow you, and gladly lay down my life for you, because, you see, I'm still a human being.

Very truly yours,

George S. Perkins

... S. Hoover Street

Los Angeles, California

Act 1 - Scene 2

Living room of Chuck Fink

When the curtain rises, another letter is projected on the screen. This one is written in a small, uneven, temperamental handwriting:

Dear Miss Gonda,

The determinism of duty has conditioned me to pursue the relief of my fellow men's suffering. I see daily before me the wrecks and victims of an outrageous social system. But I gain courage for my cause when I look at you on the screen and realize of what greatness the human race is capable. Your art is a symbol of the hidden potentiality which I see in my derelict brothers. None of them chose to be what he is. None of us ever chooses the bleak, hopeless life he is forced to lead. But in our ability to recognize you and bow to you lies the hope of mankind.

Sincerely yours,

Chuck Fink

... Spring Street

Los Angeles, California

Act 1 - Scene 3

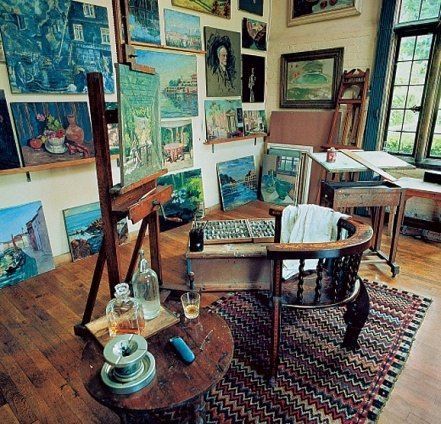

Studio of Dwight Langley

The screen unrolls a letter written in a bold, aggressive handwriting:

Dear Miss Gonda,

I am an unknown artist. But I know to what heights I shall rise, for I carry a sacred banner which cannot fail—and which is you. I have painted nothing that was not you. You stand as a goddess on every canvas I've done. I have never seen you in person. I do not need to. I can draw your face with my eyes closed. For my spirit is but a mirror of yours.

Someday you shall hear men speak of me. Until then, this is only a first tribute from your devoted priest—

Dwight Langley

... Normandie Avenue

Los Angeles, California

Lights go out, screen disappears, and stage reveals studio of DWIGHT LANGLEY. It is a large room, flashy, dramatic, and disreputable. Center back, large window showing the dark sky and the shadows of treetops; entrance door center Left; door into next room upstage Right. A profusion of paintings and sketches on the walls, on the easels, on the floor; all are of KAY GONDA; heads, full figures, in modern clothes, in flowering drapes, naked.

Act 2 - Scene 1

Temple of Claude Ignatius Hix

The letter projected on the screen is written in an ornate, old-fashioned handwriting:

Dear Miss Gonda,

Some may call this letter a sacrilege. But as I write it, I do not feel like a sinner. For when I look at you on the screen, it seems to me that we are working for the same cause, you and I. This may surprise you, for I am only a humble Evangelist. But when I speak to men about the sacred meaning of life, I feel that you hold the same Truth which my words struggle in vain to disclose. We are traveling different roads, Miss Gonda, but we are bound to the same destination.

Respectfully yours

Claude Ignatius Hix

... Slosson Blvd.

Los Angeles, California

Act 2 - Scene 2

Drawing room of Dietrich von Esterhazy

The letter projected on the screen is written in a sharp, precise, cultured handwriting:

Dear Miss Gonda,

I have had everything men ask of life. I have seen it all, and I feel as if I were leaving a third-rate show on a disreputable side street. If I do not bother to die, it is only because my life has all the emptiness of the grave and my death would have no change to offer me. It may happen, any day now, and nobody—not even the one writing these lines—will know the difference.

But before it happens, I want to raise what is left of my soul in a last salute to you, you who are that which the world should have been.

Morituri te salutamus.

Dietrich von Esterhazy

Beverly-Sunset Hotel

Beverly Hills, California

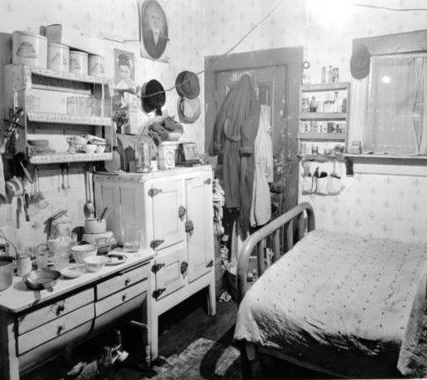

Act 2 - Scene 3

Garret of Johnnie Dawes

The letter projected on the screen is written in a sharp, uneven handwriting:

Dear Miss Gonda,

This letter is addressed to you, but I am writing it to myself.

I am writing and thinking that I am speaking to a woman who is the only justification for the existence of this earth, and who has the courage to want to be. A woman who does not assume a glory of greatness for a few hours, then return to the children-dinner-friends- football-and-God reality. A woman who seeks that glory in her every minute and her every step. A woman in whom life is not a curse, nor a bargain, but a hymn.

I want nothing except to know that such a woman exists. So I have written this, even though you may not bother to read it, or reading it, may not understand. I do not know what you are. I am writing to what you could have been.

Johhnie Dawes

... Main Street

Los Angeles, California

Act 2 - Scene 4

Entrance hall in the residence of Kay Gonda

Entrance hall in the residence of KAY GONDA. It is high, bare, modern in its austere simplicity. There is no furniture, no ornaments of any kind. The upper part of the hall is a long raised platform, dividing the room horizontally, and three broad continuous steps lead down from it to the foreground. Tall, square columns rise at the upper edge of the steps. Door into the rest of the house downstage in wall Left. The entire back wall is of wide glass panes, with an entrance door in the center. Beyond the house, there is a narrow path among jagged rocks, a thin strip of the high coast with a broad view of the ocean beyond and of a flaming sunset sky. The hall is dim. There is no light, save the glow of the sunset.

At curtain rise, MICK WATTS is sitting on the top step, leaning down toward a dignified BUTLER who sits on the floor below, stiff, upright, and uncomfortable holding a tray with a full highball glass on it. MICK WATTS’ shirt collar is torn open, his tie hanging loose, his hair disheveled. He is clutching a newspaper ferociously. He is sober.